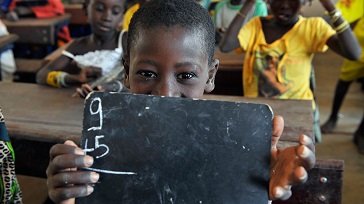

Far too many children, adolescents and youth (264.3 million) are currently out of school due to a number of factors relating to their living conditions, financial constraints and social adversities. Education is a key to end this roadblock, escape poverty, end child labour and lead a life of dignity. However, a lot needs to be done to improve access and inclusion of children in mainstream education, especially the most vulnerable and marginalised such as children in child labour and slavery.

Estimates from the World Inequality Database on Education suggest that, in lower-middle-income countries, children from the poorest 20% are eight times as likely to be out of school as children from the richest 20% (UNESCO, 2017b).This means that it is mainly the poor that miss out on schooling the most, and are thus pushed into exploitative and slavery like conditions. Thus to ensure that children from the lower and middle income countries and poor households in even the developed world do not miss out on their right to education, the direct costs of education to families need to be eliminated. Moreover, in many countries reducing the indirect costs of education is also critical through cash transfers, scholarships and incentives to students. An impact evaluation study by UNESCO on 19 conditional cash transfer programmes operational in 15 countries showed that attendance increased by 2.5% in primary schools and by 8% in secondary schools. These programmes have a stronger impact when they are combined with grants, infrastructure or other resources for schools.

Education provides people with knowledge and skills that increase their productivity and make them less vulnerable to risks. On an average, one year of education is estimated to increase wage earnings by 10% and in sub-Saharan Africa by as much as 13%. It is also said that workers with secondary education are more likely to be employed than youth and adults, with only primary education. Thus it is important to note that completion of secondary schooling is thus vital to increasing growth and reducing inequality and poverty.

Education is also said to increase resilience, as it prepares individuals to cope with risks for themselves and their family members throughout the life cycle such as health epidemics, conflicts and natural disasters. Given that currently 35 countries across the world are conflict and disaster ridden, ensuring children in these countries do not miss out on education is highly critical. Studies show that increased secondary education in Asia can especially have a strong impact on the predicted global pattern, as the continent is home to some of the largest populations, many of whom reside in coastal areas where most disasters occur (UNESCO, 2016).

Education also empowers girls and women and gives them more opportunities to make choices. It can boost their confidence and perception of freedom. It can also alter the perceptions of men influencing gender stereotypes and decreases incidents on gender based violence. It further protects young girls and boys, as well as men and women from exploitation in the labour market, for example by increasing their opportunities to obtain secure contracts. In urban El Salvador, only 7% of working women and men with less than primary education had an employment contract, leaving them very vulnerable. By contrast, 49% of those with secondary education had signed a contract (UNESCO, 2014a).

Therefore, as global primary out-of-school rate has remained stubbornly at 9% for eight years in a row, it is time that the governments commit to investing more in the education sector and accelerates the efforts to increasing access to quality, inclusive and equitable primary and secondary education. With MDGs taking lead in promoting primary school enrolments, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) play an essential role in moving beyond primary education and focus on attainment of secondary education as it clearly suggests from the examples above, that it could halve global poverty-which is one of the leading factors of pushing children into child labour and making them vulnerable to getting trafficked into labour and sexual exploitation.

On this International Literacy Day, Global March is thus committed to promote education for all and aims to use it as an effective strategy to end child labour along with providing sustainable community based solutions and mass awareness raising on the importance of education.

We are all for education for all. Are you?

Find more information on www.globalmarch.org and join us on Facebook & Twitter.

Posted by Global March at 03:50 No comments:

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest

TUESDAY, 1 AUGUST 2017

Trafficking and Forced Labour in Global Supply Chains – The Gender Lens

In recent years, those concerned with the issues of trafficking, forced labour and slavery have begun to focus on supply chains as a new arena of action with a focus on girls and young women. Millions of people including women, men and children continue to toil in forced labour for the private economy that reaps some $150 billion in profits each year (ILO report, Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour , 2014).Thousands of goods and services bought and sold every day are touched by modern-day slaves, in particular girls and young women who are not only the most vulnerable to being exploited, but also comprise of the most invisible labour in global supply chains.

Girls and young women working in global supply chains such as in the garment and seafood industry are most at risk of being victims of unfair practices, violence and slavery. Factors such as the large mixed movements of refugees and migrants, as well as conflict and natural disasters, often create an environment for trafficking and slavery. Traffickers often use sexual violence and physical abuse in addition to debt bondage to compel labour, in particular towards girls and young women.

The key issues in addressing the problem of trafficking of girls and young women within the global supply chains are –

- The complexities of the global supply chains with multiple tiers of production from large factories to home-based units, which are extremely fragmented

- Lack of transparency, making the monitoring of the supply chains and identification of trafficked workforce truly challenging

- The challenges in identifying the trafficking victims which not only makes them vulnerable to violence and labour exploitation but also invisible in the workforce

In order to address these key issues for the prevention of trafficking of girls and young women and their forced recruitment in the global supply chains, it is essential to look into the trafficked workforce “hotspots” and situations such as high levels of migration. In the era of globalization and mass production, the developed countries look out for cheap labour from the ‘backward’ economic zones such as South Asia. As industries become more competitive, it creates circumstances for employing the migrants who are often trafficked for labour exploitation. For instance the readymade garment-manufacturing sector in Bangladesh accounts for over 80% of the nation’s export earnings, has around 4 million workers, with an estimated workforce of 55-60% [1] girls and young women and ample evidences of forced and child labour. Many workers comprise the migrant population with boys and girls of all ages often voluntarily working or being trafficked.

While trafficking, forced labour and other forms of slavery in the garment sector in global supply chains, has long been an area of concern, seafood industry is one of the most overlooked area and at the same time one of the most precarious sectors to work in. Estimates from countries such as Bangladesh and Philippines- that are a source, destination and transit country for girls and young women subjected to sex trafficking, all indicate instances of child and forced labour in fisheries with frequent reportings of of sexual abuse, labour law violations and children engaged as swimmers and divers, often working for nine hours without a break in extremely unsanitary conditions.

According to the 2013 Philippine Fisheries Profile, Philippines ranks seventh among the top fish producing countries of the world. With a history and present consisting of trafficked and migrant workforce, there are also reports of girl child labour working in the processing plants at shrimp processing, freezing, and packaging factories. Young girls and boys are often forced to become fishers or fish workers, leading to disruption in their education. While young boys are employed to fishing and swimming in the dangerous waters, young girls work in the cleaning and packaging of the seafood that enhances their invisibility even more. The seafood industry is one of the most significant industries for trade between many South Asian and South East Asian and Western and European nations. The complexity of its supply chains ignores where its major chunk of workforce is coming from and instead focuses on the product, which is a concern for how accountable the supply chain process is. For instance, many seafood companies’ certification of the product is based on the quality of the product but not on its labour laws and recruitment policies. Supply chain accountability for industries such as the seafood with extended global supply chains is therefore extremely crucial to a company policy on human rights and ethical sourcing.

No industry or region is fully insulated from the social deficit which has emerged

from the rise of the modern global economy, and all leading multinational corporations have come to recognize the risks associated with ever-expanding supply networks. Thus, for businesses to be able to adequately identify and address the issue of trafficking of girls and young women it is important build the understanding to plug the knowledge gaps of human trafficking, forced and gender related issues of the geographical region of the workforce. A close co-operation with local stakeholders, such as NGOs and CSOs, is of crucial importance to understand where they are forced to work and why the conditions lend themselves to human trafficking. Understanding the local complexities of the geographically fragmented garment and seafood industry, where cultural notions may also be used to justify the curtailment of women and child rights, the local stakeholders can play a major role in mainstreaming gender in the prevention strategies of trafficking, focusing on the protection of girls and young women.

Global March thus aims to encourage companies to take trafficking seriously not only for moral or ethical reasons, or for them to see it as a ‘risk’ for their companies but as an overall responsibility towards their product and the people involved. The absence of a responsible approach combined with the incapacity or unwillingness of foreign governments to protect the rights of girls and young women and their vulnerability created by poverty, inequality and discrimination is the biggest threat to achieving sustainable gender equality. We need to collectively act for the well being and livelihoods of young girls and boys and address the issue of trafficking, forced labour and slavery within a wider context of labour rights and working conditions. We also need to be clear about who is facing the greatest risks: it is workers, not corporations, but the onus to mitigate the risk lies with the latter.

Thus, if you as a reader own any company yourself or work in a manufacturing company, why not take a peep into your company’s supply chain and see who is producing the actual product? If you were in the shoes of the workers, will you be able to take all that they are enduring? What can you do in your capacity to protect the workers from exploitation, trafficking and child labour? These are the questions you must ask yourself today, tomorrow and every day!