By Isaac Ruiz Sánchez

In Peru, as in the rest of Latin America, three months of a pandemic have exposed great pre-existing inequalities, which have long prevented the exercise of human rights of the most vulnerable population. The pandemic has rendered millions of children and adolescents in a situation of social exclusion, poverty and discrimination (especially those who have been working from an early age and in hazardous activities). COVID-19 has further exposed the discrimination of children and adolescents living in rural areas, ones belonging to indigenous communities, and ones with disability and differential gender and sexual identity.

A child working in agriculture in the town of Carapongo, on the outskirts of Lima. (Photo change.org)

A child working in agriculture in the town of Carapongo, on the outskirts of Lima. (Photo change.org)

It never rains but it pours

The rate of child labour in Peru is amongst the highest in Latin America. According to the mapping carried out last year by the Global March Against Child Labour, 21.8% of children between the ages of 5 and 17 years (1.6 million) were in child labour however, the percentage is believed to be higher because of under-registration of girls and adolescent women. The latest data from the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) indicates that child labour decreased by 4.3% between 2012 and 2018, with a lower current figure of 1.1 million children and adolescents, of which the vast majority are below the minimum age to work, (14 years in Peru), one of the lowest in the region. The proportion is five times higher in rural areas, and 99.6% of adolescents work in the informal economy.

In the last three years, Peru has received more than 860,000 Venezuelan migrants and refugees, including 160,000 children and adolescents, in some cases without the accompaniment of family members. According to the Ministry of Education, only 56,000 were in school before the pandemic. Their families have not been considered in the government’s financial aid programmes, despite being in a situation of extreme vulnerability. One of the most serious impacts of the pandemic on these children and adolescents is the deterioration of their mental health, also having to endure xenophobic insults and discriminatory treatment.

One of the harshest effects of the pandemic on children and adolescents in vulnerable situations and on their families is hunger caused by the loss of income. The impact would have been even worse if many families would have not organised to prepare food collectively, in what is called “ollas comunes” (communal pots). In the country, 8.1 million people were left without work and poverty grew by 10%. Almost a third of the recipient families did not receive the government-issued voucher, and 83.2% of those who received it were unable to cover the minimum monthly expenses.

Photo: CESIP Archive

Photo: CESIP Archive

The closure of schools has left many children and adolescents without education. Although the government promptly launched the “Aprendo en casa” (I learn at home) strategy, a large part of students are not being able to access virtual classes, because in Peru only 3 out of 10 families have internet and a computer at home, and in rural areas only 6%. Additionally, during the first two months of the quarantine, children and adolescents did not receive food which is distributed in public schools via the “Qali Warma” programme.

When this article was written, boys and girls have already been in confinement for 100 days. Paradoxically, staying at home increases the risk of being victims of mistreatment and sexual abuse. During the confinement, there have been 23 femicides and 350 rapes and other sexual assaults on minors.

Children and adolescents who live or are linked to the street have simply been left with no place to live.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child labour

Photo: CESIP Archive

Photo: CESIP Archive

The truly devastating economic impact of the pandemic places the future of child labour on a bleak forecast. Specialists calculate that the fall in GDP in Peru will be 12%, more than double the decrease for the rest of Latin America at 5.3%, calculated by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Unemployment and the reduction of self-employment are reaching unprecedented figures, causing the informal economy to increase, which in Peru already occupies more than 70% of the Economically Active Population (EAP). Almost all micro-businesses are on the verge of bankruptcy, and many others are not able to access the credits that the State is granting. Poverty and extreme poverty will continue reaching millions of people.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that it is very likely that child labour, especially hazardous work, will increase between 1% and 3% in the region, between 109 thousand and 300 thousand children and adolescents. This would be a setback compared to the progress made in recent years, moving away from the prospect that Latin America and the Caribbean would become the first developing region to eradicate child labour, and reach the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 8.7 on ending child labour by 2025.

What needs to be done?

The Peruvian government began facing the pandemic with an agenda called “primero la vida” (life first), including compulsory confinement but with the granting of economic vouchers and food baskets for the subsistence of the most vulnerable families since they could not go out to work. However, it gradually turned towards a “reactivación económica” (economic reactivation) agenda, giving priority to the progressive opening of economic activities, without giving continuity to social protection measures.

At this moment, the country is in the dilemma between ending or continuing with the quarantine. Economic reasons push the government to end compulsory confinement, but from a public health perspective, and according to many specialists, Peru is at the worst stage to end confinement. Specialists have further advised to maintain it even with the risk of aggravating the economic situation. It is highly probable that in the immediate future, the reactivation of companies, which is needed, will continue to be favoured, but it is worrying to see the State neglect its obligation to protect the most vulnerable sectors.

We as civil society demand for priority to the protection of the rights of children and adolescents, especially those who are at risk of entering the labour market too early and performing hazardous activities (due to their situation of poverty, for living in rural areas, belonging to native or indigenous communities, or being migrants or refugees). It is unacceptable that the State looks the other way, leaving families with no other option but to have child labour as a way to mitigate the lack of income.

Photo: CESIP Archive

Photo: CESIP Archive

Many of the proposals that we made in 2019, as Global March Against Child Labour in the region, towards the achievement of Target 8.7 of the SDGs are more relevant today. First, to put into practice the “prioridad por la infancia” (priority for children), allocating resources in national budgets for specific policies on the protection of children and adolescents from child labour and its worst forms, educational exclusion, violence, exploitation. No child or adolescent, nor their families, should be left behind.

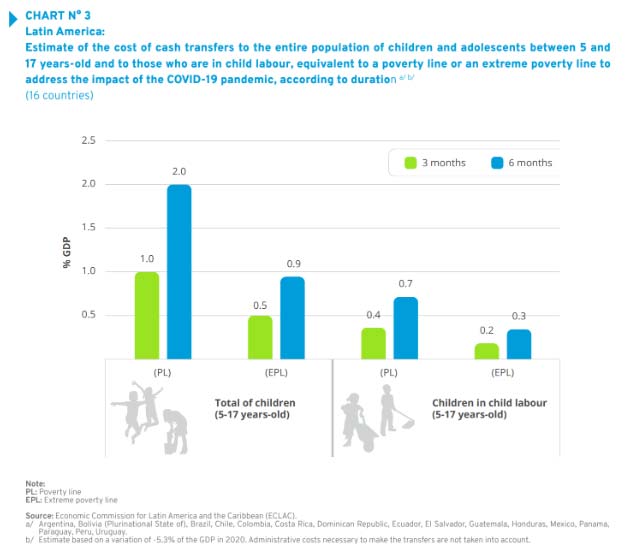

According to ECLAC, protecting the well-being of children and adolescents in Peru, through temporary monetary transfers to the families of children and adolescents in child labour situations, would cost just 0.2% of GDP for 3 months, and 0.3% for 6 months. Considering that the Peruvian government plans to invest 12% of its GDP to face the effects of the pandemic, this distribution is possible. One way to do this is via the “Juntos” cash transfer programme, (including families where child labour exists), that aims to prevent boys and girls from entering child labour and prevent adolescents from performing hazardous activities, along with guaranteeing no interruption to their education.

Moreover, today more than ever, the Ministry of Education must strengthen inclusive educational modalities, aimed at favouring the access and permanence of inclusion of children and adolescents in child labour situations in the school system, and developing strategies that promote a smooth transition from school to work. Several of these strategies already exist formally but are not implemented.

Further, the rural areas possess the lowest tiers of the supply chains of products that go to the national and international market, in which child labour and forced labour have been identified. To prevent an increase in child labour, it is necessary to strengthen labour inspection and to count on a greater commitment from the business sector. The Ministry of Labour must not back down in promoting the “Sello Libre de Trabajo Infantil” (Child Labor Free Seal) recognition.

Last but not least, it is necessary to carry out stronger action to make child labour socially and politically visible as an intolerable violation of the rights of children and adolescents. Child labour is a very normal and tolerated problem in Peruvian society, even by the institutions that claim to protect children and adolescents. As long as there is no conviction that child labour must be eradicated and there is no strong social and citizen-led demand for its attention, the government will not prioritise it.

Photo: CESIP Archive

Photo: CESIP Archive

A great opportunity approaches with 2021, which is already a few months away. The year 2021 has been declared by the United Nations General Assembly as the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour. On this line, the Peruvian government became one of the Pathfinder Countries of Alliance 8.7, explicitly committing itself to accelerate the rate of reduction of child labour, with a national policy on the subject. This is the time to uphold this commitment and move forward towards a child labour free Peru. This is the moment.

Isaac Ruiz Sánchez is a member of CESIP – “Centro de Estudios Sociales y Publicaciones” (Center for Social Studies and Publications). He is a representative of civil society in the Steering Committee for the Prevention and Eradication of Child Labour in Peru (CPETI) and coordinates the activities of Global March Against Child Labour in his country.

___________________________

La pandemia en Perú: derechos de la niñez y adolescencia en crisis

Isaac Ruiz Sánchez*

En el Perú, como en el resto de Latinoamérica, tres meses de pandemia han desnudado las grandes desigualdades existentes, que desde hace mucho impiden el ejercicio de los Derechos Humanos de la población en mayor vulnerabilidad. La pandemia encuentra a millones de niños, niñas y adolescentes en situación de exclusión social y pobreza, trabajando desde muy temprana edad y en actividades peligrosas, discriminados por vivir en el área rural y por pertenecer a pueblos originarios, por tener alguna discapacidad o por razones de género e identidad sexual.

Niño trabajando en la agricultura en la localidad de Carapongo, en las afueras de Lima. (Foto change.org)

Niño trabajando en la agricultura en la localidad de Carapongo, en las afueras de Lima. (Foto change.org)

Lloviendo sobre mojado

Los niveles de trabajo infantil en Perú son de los más elevados de Latinoamérica. Según el Mapeo realizado el año pasado por la Marcha Global contra el Trabajo Infantil, 21.8% de personas de 5 a 17 años (1,6 millones) estaba en esta situación, y el porcentaje sería mayor porque hay un subregistro de niñas y adolescentes mujeres. Últimos datos del INEI, indican que el trabajo infantil disminuyó en 4.3% entre 2012 y 2018, siendo la cifra actual de 1,1 millones de niños, niñas y adolescentes, la gran mayoría por debajo de la edad mínima, que en Perú es 14 años, una de las más bajas de la región. La proporción es cinco veces mayor en el área rural, y 99.6% de adolescentes trabaja en la economía informal.

En los últimos tres años el Perú ha recibido más de 860,000 migrantes y refugiados venezolanas, entre ellos 160 mil niños, niñas y adolescentes, en algunos casos sin acompañamiento de familiares. Según el Ministerio de Educación, sólo 56,000 estaban en la escuela antes de la pandemia. Sus familias no han sido consideradas en los programas de ayuda económica del gobierno, pese a estar en una situación de vulnerabilidad extrema. Uno de los impactos más graves de la pandemia en estos niños, niñas y adolescentes es el deterioro de su salud mental, teniendo además que soportar insultos xenofóbicos y trato discriminatorio.

Uno de los más duros efectos de la pandemia sobre la niñez y adolescencia en situación vulnerable y sobre sus familias es el hambre por la pérdida de ingresos. Si no hubiera sido porque muchas familias se organizaron para preparar los alimentos en forma colectiva, en “ollas comunes”, el impacto hubiera sido aún mayor. En el país, 8,1 millones de personas se quedaron sin trabajo y la pobreza creció en 10%. Casi un tercio de las familias destinatarias no recibieron el bono otorgado por el gobierno, y al 83.2% de las que lo recibieron no les alcanzó para cubrir los gastos mínimos mensuales.

Foto: Archivo CESIP

Foto: Archivo CESIP

El cierre de las escuelas ha dejado sin educación a muchos niños, niñas y adolescentes. Aunque el gobierno lanzó prontamente la estrategia “Aprendo en casa”, gran parte de estudiantes no están pudiendo acceder a las clases virtuales, porque en Perú solo 3 de cada 10 familias cuentan con internet y computadora en casa, y en el área rural sólo el 6%. Adicionalmente, durante los dos primeros meses los niños, niñas y adolescentes perdieron la alimentación recibida a través del programa Qali Warma, que se distribuye a través de las escuelas públicas.

Al momento de escribir estas líneas, niños, niñas y adolescentes ya llevan 100 días de encierro. Paradójicamente, permanecer en casa acrecienta el riesgo de ser víctimas de maltrato y de abuso sexual. Durante el confinamiento se han producido 23 feminicidios y 350 violaciones y otras agresiones sexuales a personas menores de edad.

Los niños, niñas y adolescentes que viven o que están vinculados a la calle, se han quedado simplemente sin lugar para vivir.

Los efectos de la pandemia de la COVID-19 en el trabajo infantil

Foto: Archivo CESIP

Foto: Archivo CESIP

El impacto económico de la pandemia, realmente devastador, coloca el futuro del trabajo infantil en pronóstico reservado. Especialistas calculan que caída del PBI en el Perú será de 12%, más del doble del decrecimiento que tendrá América Latina, calculado por CEPAL en 5,3%. La reducción del empleo por cuenta propia y el desempleo alcanzan cifras nunca vistas; esto está haciendo que se incremente la economía informal, que en el Perú ya ocupa a más del 70% de la PEA; casi todas las microempresas se encuentran al borde de la quiebra, y muchas sin poder acceder a los créditos que el Estado está otorgando. La pobreza y la pobreza extrema continuará envolviendo a millones de personas.

La OIT estima que es muy probable que el trabajo infantil, especialmente el trabajo peligroso, se incremente entre 1% y 3% en la región, entre 109 mil y 300 mil niños, niñas y adolescentes. De ser así, se produciría un retroceso respecto a los avances sostenidos en los últimos años, alejándose la posibilidad de que América Latina y el Caribe se convierta en la primera región en desarrollo en erradicar el trabajo infantil, y alcanzar la Meta 8.7.

¿Qué hacer?

El gobierno peruano empezó a hacer frente a la pandemia con una agenda que denominó “primero la vida”, acompañando la inamovilidad social obligatoria con el otorgamiento de bonos económicos y canastas de alimentos para la subsistencia de las familias más vulnerables mientras no puedan salir a trabajar. Pero poco a poco fue haciendo un viraje hacia una agenda de “reactivación económica”, dando prioridad a la apertura progresiva de las actividades económicas, sin dar continuidad a las medidas de protección social.

En este instante, el país se encuentra en la disyuntiva entre dejar atrás o continuar con la cuarentena. Las razones económicas empujan al gobierno a terminar con el confinamiento obligatorio, pero desde el punto de vista de la salud el Perú está, según muchos especialistas, en el peor momento para dejar la inamovilidad social, por lo que aconsejan mantenerla, aún con el riesgo de agravar la situación económica. Es muy probable que en el futuro inmediato se continúe privilegiando la reactivación de las empresas, que es necesaria, pero preocupa que el Estado deje de lado su obligación de proteger a los sectores más vulnerables.

Desde la sociedad civil demandamos prioridad a la protección de los derechos de la niñez y adolescencia, especialmente de quienes están en riesgo de incorporarse precozmente al mercado de trabajo y a actividades peligrosas, por la situación de pobreza, vivir en el ámbito rural, pertenecer a pueblos originarios o indígenas, ser migrantes o refugiados. Es inaceptable que el Estado mire hacia otro lado, dejando que las familias tengan que acudir al trabajo infantil como forma de mitigar la falta de ingresos.

Foto: Archivo CESIP

Foto: Archivo CESIP

Muchas de las propuestas que hicimos en 2019, agrupados en la Marcha Global contra el Trabajo Infantil, para el cumplimiento de la Meta 8.7 de los ODS están vigentes y cobran mayor actualidad. La primera, es llevar a la práctica la “prioridad por la infancia”, asignando recursos en el presupuesto nacional para las políticas específicas de protección especial de la niñez y adolescencia del trabajo infantil y sus peores formas, la exclusión educativa, la violencia, la explotación. Ningún niño, niña o adolescente, ni sus familias, deben quedarse atrás.

Foto: Archivo CESIP

Foto: Archivo CESIP

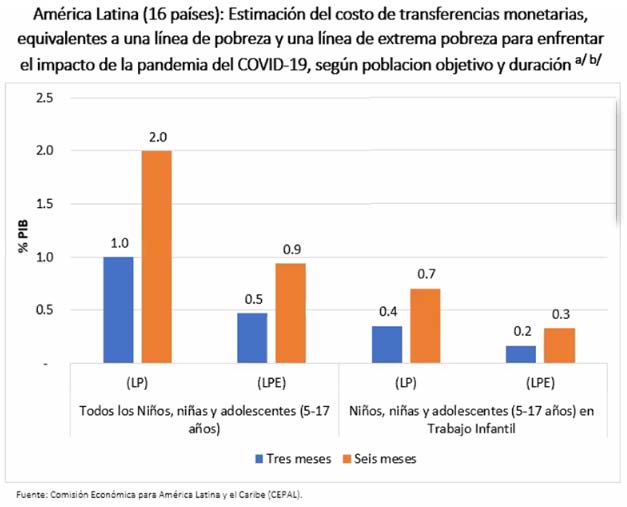

Según CEPAL, resguardar el bienestar de niños, niñas y adolescentes en Perú, a través de transferencias monetarias transitorias a las familias de niños, niñas y adolescentes en situación de trabajo infantil, tendría un costo de apenas 0.2% del PBI por 3 meses, y de 0.3% por un semestre. Si se tiene en cuenta que el gobierno peruano tiene prevista una inversión del 12% de su PBI para hacer frente a los efectos de la pandemia, este desembolso es totalmente posible. Una vía para realizarlo es el Programa de transferencias monetarias Juntos, incluyendo en él a las familias en las que existe trabajo infantil, adoptando la prevención del ingreso de niños y niñas al trabajo y de adolescentes a actividades peligrosas como uno de sus objetivos específicos, garantizando que no tengan que interrumpir su educación.

De otro lado, hoy más que nunca, el Ministerio de Educación debe fortalecer las modalidades educativas inclusivas, orientadas a favorecer el acceso y la permanencia de niños, niñas y adolescentes en situación de trabajo infantil en el sistema escolar, y desarrollar estrategias que promuevan la transición sin trabas de la escuela al trabajo. Varias ya existen formalmente, pero no están implementadas.

En el área rural se encuentran los eslabones más bajos de las cadenas de suministros de productos que van al mercado nacional e internacional, en los que se ha identificado trabajo infantil y trabajo forzoso. Para prevenir su crecimiento, se necesita fortalecer la inspección laboral y un mayor compromiso del sector empresarial. El Ministerio de Trabajo no debe retroceder en el impulso del Reconocimiento “Sello Libre de Trabajo Infantil”.

Por último, pero no menos importante, es necesario llevar adelante una fuerte acción para visibilizar social y políticamente el trabajo infantil como una intolerable vulneración de derechos de la niñez y la adolescencia. Este es un problema muy naturalizado y tolerado en la sociedad peruana, incluso por las propias instituciones llamadas a proteger a la niñez y la adolescencia. Mientras no exista un convencimiento de que se debe erradicar el trabajo infantil y no exista una fuerte demanda social y ciudadana para que se le brinde atención, el gobierno no lo tendrá entre sus prioridades.

Una buena oportunidad para ello es que el 2021, que ya está a pocos meses, ha sido declarado por la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas como el Año Internacional para la Eliminación del Trabajo Infantil. Asimismo, el gobierno peruano, por su propia voluntad, se convirtió en uno de los Países Pioneros de la Alianza 8.7, comprometiéndose explícitamente con acelerar el ritmo de reducción del trabajo infantil, contando con una política nacional en la temática. Este es el momento.

(*) Isaac Ruiz Sánchez es miembro del CESIP – Centro de Estudios Sociales y Publicaciones. Es representante de la sociedad civil en el Comité Directivo para la Prevención y Erradicación del Trabajo Infantil de Perú (CPETI) y coordina la Marcha Global contra el Trabajo Infantil en su país.